For many Americans, mosquitoes are a year-round disturbance. These tiny, blood-thirsty insects will attach anywhere from head-to-toe, particularly during warmer months. They also carry diseases that can cause severe symptoms like fevers, diarrhea, vomiting, and even death.

Diseases carried by mosquitoes kill more people than any other living species on Earth. According to Gates Notes, more than 700,000 people worldwide die in any given year as a result of the diseases these bugs carry.

Where Do Mosquitoes Live?

Part of the reason mosquitoes are so dangerous is that they thrive is warm temperatures. Their preferred temperature is anything above 70 degrees Fahrenheit, which means they can exist for some length on every continent in the world except for Antarctica. They primarily like to live in places that:

What to Expect from Mosquitoes in 2019

With the rise of global temperatures, along with the rise of human activity, comes a better environment for mosquitoes to proliferate and spread across the world.

The warmer and wetter it is, the more mosquitoes will be around. Looking back to late 2018, a long stretch of rain (3 to 12 inches over two weeks) in Michigan caused mosquito populations to triple or quadruple. More rain means more standing water, which means more mosquitoes. Similar bouts of rain are expected in 2019, which will no doubt lead to similar increases in mosquito populations.

These warmer and wetter conditions allow diseases that mosquitoes carry to be spread quicker and easier. Currently, different parts of the world are facing outbreaks of yellow fever, dengue, Zika and chikungunya, according to a Boston Children’s Hospital study. Many parts of the U.S. still don’t have substantial communities of the primary disease-carrying mosquitoes that exacerbate outbreaks and epidemics. However, researchers believe that by 2050, almost every section of the United States will have communities of mosquitoes at some point during the year.

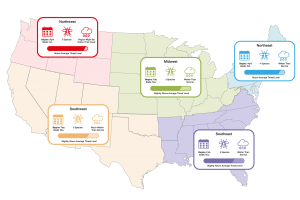

Let’s look at the five primary regions of the country and how the predicted weather for 2019 will affect the mosquito populations in the area.

The southeastern United States, which includes Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Alabama, Tennessee, and more, is the wettest, warmest part of the country. It’s a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes because it’s warm most, if not all, of the year.

The types of mosquitoes

in the Southeast include:

- Yellow fever mosquito

- Asian tiger mosquito

- Southern mosquito

- Northern house mosquito

Wetter than normal

2019 Mosquito Forecast for the Southeast

In 2019, it’s expected that these mosquito populations will be average or slightly above average. This is due to a wetter-than-normal outlook for the summer as well as temperatures that will be average or slightly above average, according to the National Weather Service.

Mosquito season will start around mid-February to early April, depending how far north your state is in the region. For example, South Florida’s mosquito season will have started in February while Tennessee’s mosquito season will start around the beginning of April once the temperatures are more consistently warm.

In the Southeast, mosquitoes may never become dormant, especially in Florida. However, if there are any stretches (a week or two) where the temperature drops below 50 at night, then mosquitoes will die down until the following year. This happens around mid-October or early November in this region.

The Northeast has some of the hottest summers in the country, and there are plenty of standing bodies of water in the region that help produce high volumes of mosquitoes. This region includes New York, Pennsylvania, the New England states, and others. The National Weather Service says that the Northeast region has a higher probability of experiencing more rain this year on average than the rest of the country.

Mosquitoes in the

Northeast include:

- Yellow fever mosquito

- Asian tiger mosquito

- Northern house mosquito

- Eastern tree hole mosquito

2019 Mosquito Forecast for the Northeast

High rates of mosquitoes are expected throughout the spring and summer in the Northeast in 2019. The expected wet weather combined with the heat—2019 is expected to be one of the six hottest years on record across the country—will bring more mosquitoes, thus the chance for more deadly diseases, to the area.

Mosquito season will start in the Northeast around mid-April or early May, and it will last until mid- to late-October. On average, nighttime temperatures in the region dip below the magical 50-degree number in October, but depending on how warm this year is, it could stretch into November.

Midwest

The Midwest is characterized by large, open plains, with cold, frigid winters. However, their summers get very hot and wet. The Midwest also has one of the higher rates of reported mosquito-borne diseases in the country, especially in states like Wisconsin, the Dakotas, Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska. These diseases include West Nile virus, dengue, and Jamestown Canyon virus, according to the CDC.

Mosquitoes in the

Midwest include:

- Asian tiger mosquito

- Northern house mosquito

- Western encephalitis mosquito

2019 Mosquito Forecast for the Midwest

Midwesterners should expect their mosquito season to start around early April to late May—again, whenever the temperatures rise above 50 degrees at night for a stretch of about a week. Thankfully for many in the region, mosquito season doesn’t last as long as it does in many other parts of the country. Mosquito season usually ends around the beginning-to-middle of October.

During the 2019 mosquito season, there’s about a 50 percent chance of having a hotter, wetter summer in the Midwest, according to the National Weather Service. As a result, you can expect the mosquito populations to follow suit.

Southwest

The Southwest includes southern California, Nevada, Texas, Arizona, and other states. Sure, much of this region of the country is characterized by arid temperatures in the desert areas, but all mosquitoes need is a little bit of standing water to go along with the hellacious temperatures for much of the year. States like Arizona and California have seen cases of Zika, West Nile, and Chikungunya in previous years, and the rest of Southwest can still have a solid mosquito population if conditions are right.

Mosquitoes in the Southwest include:

- Yellow fever mosquito

- Asian tiger mosquito

- Northern house mosquito

- Southern mosquito

- Western encephalitis

Mosquito Season

Begins: February-April

Ends: Mid-October or Early November much wetter than normal due to the 2019 El Niño weather pattern

2019 Mosquito Forecast for the Southwest

The Southwest has already seen a wetter-than-usual beginning of 2019 due to the El Nino weather pattern. The conditions are supposed to stay like this for the rest of the spring and summer, and when you pair that with the hot temperatures of the region, mosquito populations are expected to be higher than normal, too.

Mosquito season in the Southwest usually starts early in the year around March and can last all the way to the end of the year. Temperatures consistently stay above 60 at night in the region well into November and December.

Like the other regions of the country, the Northwest also deals with mosquitoes on a consistent basis. This includes states like Washington, Oregon, Montana, and Idaho as well as northern California. The Northwest has seen cases of West Nile virus, Zika, Chikungunya, and more in previous years.

Mosquitoes in the Midwest include:

- Northern mosquito

- Western encephalitis mosquito

- Eastern tree hole mosquito

50 to 80 percent chance the region will be hotter and wetter than usual

2019 Mosquito Forecast for the Northwest

The mosquito season in the Northwest starts around mid-April and lasts until early October. The National Weather Service says there is a 50 to 80 percent chance the region will be hotter than usual, and the Northwest is expected to get more precipitation throughout the summer of 2019 than usual, too.

Thankfully for many in the Northwest, the rainy season hardly overlaps with mosquito season. However, years like 2019 where there is expected to be more rain in the summer than usual means there will most likely be more mosquitoes throughout the region this year, too.

Hawaii and Alaska

Hawaii and Alaska could not be more different with regard to mosquito populations. Hawaii shares similar patterns with the Southeast, namely south Florida. Hawaii’s mosquito season lasts nearly all year, from early February until December. However in Alaska, mosquitoes—mainly the northern house mosquito—are only populous for a few months during the summer, from June to August.

Yellow fever Mosquito (Aedes aegypti):

Yellow fever mosquitoThese mosquitoes spread diseases like the Yellow fever, dengue fever, Zika, and chikungunya. Despite their prevalence in more parts of the country, Yellow fever mosquitoes aren’t as high in population as the Asian tiger mosquito.

Southern Mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus):

Head lice move all around your head while they live there to find the premium real estate for blood sucking. Because of this, they move around frequently, especially as the population on your head grows. The scalp is a very sensitive area, so you or your child should be able to feel something moving from one area to the next. Head lice moving across the scalp may also cause a tickling sensation that could result in scratching the area.

Asian Tiger Mosquito (Aedes albopictus):

The Asian tiger mosquito is confined to the Southeast, and in similar locations as the Yellow fever mosquito. The University of Florida says that the decline in Yellow fever mosquitoes correlates with the rise in Asian tiger mosquitoes. These mosquitoes can transfer diseases such as dengue fever and Eastern equine encephalitis.

Other mosquitoes with smaller populations across the country include the Western encephalitis mosquito, the Eastern tree hole mosquito, the Malaria mosquito, and the black-tailed mosquito.

With all of these mosquitoes, the males live for about a week or two, and the females live around a month and a half or two.

What Diseases Do Mosquitoes Carry?

It bears repeating that mosquitoes are more than just nuisances that lead to itchy skin—they also carry deadly diseases.

The primary diseases they carry include:

Malaria

This is most deadly mosquito-borne disease. In 2015, there were hundreds of millions of cases of malaria reported, and nearly 500,000 deaths because of the disease. This makes up more than half of all deaths that come from mosquito-borne illnesses. The primary symptoms of malaria are a high fever, chills, nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting.

Yellow fever

This disease is named after the yellow-ish hue it can cause in patients as a result of jaundice (a condition that affects the liver), which is a symptom of yellow fever. Other symptoms include headaches, fever, and fatigue. Yellow fever is a highly fatal disease if it’s contracted—half the people who get it die within a week to 10 days, according to the World Health Organization. However, it is preventable with a vaccination. It is currently most prevalent in Central America, South America, and Africa, and it causes between 30,000 and 60,000 deaths per year.

West Nile virus

The West Nile virus can be largely asymptomatic, but 20 percent of people who get the disease develop symptoms such as a fever, diarrhea, a stiff neck and swollen lymph nodes, and muscle weakness. The virus can develop to the point where it starts to impact your central nervous system, too, which causes violent convulsions and paralysis. There were more than 2,500 West Nile cases reported in the United States in 2018, according to the CDC.

Zika

This disease is largely asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic. If it does show symptoms, they may appear in the form of a fever, skin rashes, headaches, joint pain, and more. However, Zika has proven to have more severe effects on pregnant women and led to babies being born with brain and head defects. Zika was at the center of a worldwide epidemic in the 2000s and 2010s in the Americas and Asia, during which it was expected that about 30,000 people were affected.

Japanese encephalitis

Similar to the aforementioned mosquito-borne diseases, Japanese encephalitis reveals itself with vomiting, headaches, a high fever, and joint and muscle pain. The symptoms take anywhere from a few days to two weeks to show up after you’ve been bitten. The disease is present in mosquitoes ranging from northern Asia all the way to almost every tropical region in the world, according to the CDC. There is a vaccine for Japanese encephalitis.

It should be noted that just because you are bit by a mosquito, it doesn’t mean you have been infected with a disease. Symptoms typically don’t show up for these disease until at least a couple days after you’ve been bit. If you plan on traveling to an area, like South America or East Africa, where rates of mosquito-borne diseases are higher than in America, there are preventative steps you can take to help reduce your risk of getting bit, which overall reduces your risk of getting a mosquito-borne disease.

Unfortunately, mosquitoes are most attracted to the carbon dioxide we emit. While we are never going to stop emitting CO2, you can help to reduce the instances in which you are bitten by mosquitoes by considering the following tips.

1. Use Mosquito Repellent

It’s projected that the mosquito repellent industry generate almost $5 billion alone, and that doesn’t even account for sleep nets and clothing. The industry is so massive because the mosquito problem is so massive.

The forms of chemical and natural mosquito repellents include:

- DEET: The acronym for the chemical compound diethyltoluamide, DEET is the most popular mosquito repellent. It helps block the odors on your body that mosquitoes are believed to attract the bugs. It can be sprayed on the skin and on your clothes. DEET sprays come in concentrations between 4 percent and 100 percent, according to Consumer Reports. However, concentrations of 30 percent and above will all provide a similar effectiveness for the same amount of time.

- Permethrin: This highly concentrated chemical is used as a pesticide against mosquitoes and as a repellent. Permethrin is only meant to be sprayed on your clothes, so never spray it on your skin. It can last on your clothes for weeks, even if you wash them. The chemical paralyzes and eventually kills the mosquitoes.

- Picaridin: This chemical is similar to DEET, only it doesn’t irritate the skin like DEET. It has a similar effectiveness, though, and it is colorless and odorless. It’s also capable of shutting down mosquitoes’ ability to smell human odor.

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus: This solution synthetically recreates the oil of eucalyptus trees and offers a safer alternative to stronger chemical repellents. The Mississippi State Department of Health says that OLE, which is different from natural oil taken from lemon eucalyptus trees, has about a similar effectiveness to sprays with 15 to 20 percent DEET. OLE cannot be used on children younger than three.

- Natural oils: Chemical-free sprays and oils made from trees and plants like tea trees, lavender, garlic, peppermint, citronella, and more have proven to be moderately effective in preventing mosquito bites. While not as effective as DEET and other chemical-based solutions, they are a safer alternative and can be applied to children under three.

Make sure to use these repellents as directed. Avoid spraying the solutions near your face. Instead, spray an amount in your hand and then apply it to the necessary areas near your eyes, nose, and mouth.

While these repellents are most often used on your body, certain repellents can be sprayed in your yard to help prevent mosquitoes from living and laying eggs in and around your home. It should be noted that repellents, used often and in excess, can cause health problems such as eye irritation and allergic reactions, so use them in moderation.

2. Wear Proper Clothing

One of the primary steps against preventing mosquito bites is wearing proper clothing. These clothing items include:

Long-sleeve shirts

Pants

Jeans

Long socks

High-ankle boots

While clothing won’t fully stop a mosquito from biting you, it will make it more difficult for the mosquito to bite down to your skin. You should spray repellent on top of your clothing to add an extra layer of prevention. You can also find clothing that is already treated with chemical repellents to help stave off mosquitoes.

If you plan to sleep outside or the place you’re staying indoors doesn’t have closed windows, screens, or air conditioning, mosquito-repellent nets, screens, and tents help keep mosquitoes away while you are inside and sleeping. Mosquito nets and tents have thin, meshy fabric, and they’re generally hung above your sleeping area so they can cover the area below and around you. The ends of the nets are tucked under the bed or left flat on the ground. The spacing between the meshy material allows air to easily blow in and out of them while being small enough to prevent mosquitoes from flying through.

Some of these materials are treated with repellents to help increase their effectiveness. This material can be placed in windows and other openings to prevent mosquitoes from getting inside. Nets can also be used to help prevent mosquitoes from biting you while while you walk around during the day. They can be attached to hats and drape down to your shoulders and can also be tucked into your shirt. This will help protect the neck, face, and shoulder area.

4. Keep Your Yard Clean

Mosquitoes thrive in areas with a lot of clutter and standing water. Sure, you can’t help it if there are days of rain that leave optimum conditions for mosquito eggs to be laid and hatched. That being said, there are things you can do to try and prevent mosquitoes from proliferating in your yard.

Keeping your yard clean and free of standing water can help reduce the risk of mosquitoes residing in and around your home. Some things you can do around your yard include:

- Dump out pots or other objects that collect rainwater

- Clean up piles of leaves and shrubbery

- Clear out any dead trees or plants

- Clear out clogged gutters

- Collect kids toys, make sure they contain no standing water, and store them in a dry place

- Clear trash cans of any standing water

If there are parts of your driveway or patio that have divots or are slanted to a point where they leave puddles of standing water, make sure to spread the water out. It’s vital to make sure your yard is clean—not just for mosquitoes, but for other pests, too. As mentioned, mosquitoes are attracted to carbon dioxide, and we aren’t the only species that emit that. Dead plant life does, too, so make sure to take care of any dying or dead plants around your property.

5. Get Vaccinated

Vaccines have been developed to help prevent against some mosquito-borne disease. There are vaccines to help prevent against yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and a handful of other mosquito-borne diseases. On the flip side, there are many mosquito-borne diseases there are no vaccines for, including malaria and WNV. Make sure you get all the necessary vaccines before living in or visiting places where you are at risk of being infected with a preventable mosquito-borne disease.

If you have any questions regarding mosquitoes, the diseases they’re carrying, and how they are affecting your area, or if you have any mosquito problems at all, contact a local pest control company. If you suspect you have any sort of health risks that came from a mosquito bite, contact a doctor immediately.

Make sure to stay up-to-date with the latest mosquito forecast for your area. Websites like the Weather Channel provide daily mosquito activity updates that can let you know whether you should be wearing mosquito repellent or taking other preventative steps throughout your day.

How We Predict Mosquito Populations for 2019

To reach our conclusions on mosquito forecasts, we studied historical weather datasets and analyzed a number of predictive weather models, including the trends of major weather events (including hurricanes, floods, and weather patterns such as El Niño) from:

- The National Weather Service

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF)

- The World Meteorological Organization (WMO)

In addition, we factored in mosquito data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The weather models showed how likely it was that precipitation totals and temperatures would be higher or lower than average during each month of the year. We took these weather models and compared them to where mosquitoes are present and are becoming more populous in each region of the country.

Once we distilled, cross-referenced, and computed the data, we came to reasonable conclusions based on logic and general mosquito trends over time.